VCU Police maps road to reform

VCU Police review efforts to meet the community’s public safety needs in a holistic and inclusive way

By Corey Byers

Since his arrival in 2010 at Virginia Commonwealth University, John Venuti’s challenge, in his words, has been “to make VCU the safest university in the United States.”

Venuti, associate vice president for public safety and chief of police, is making progress toward that goal, according to statistics. On-campus robberies, for example, have declined from a high of 18 in 2011-12 to a low of two this academic year. And a spring 2020 survey reports that 97% of students, faculty and staff feel “safe” or “very safe.”

Social unrest last summer presented Venuti with a new challenge: stepping up the department’s commitment to equity and social justice so that everyone feels safe when they need VCU Police. At the same time, VCU President Michael Rao, Ph.D., announced that the university would develop a new transdisciplinary model for campus safety and wellness, and an independent committee, the Safety and Well-being Advisory Committee, was established to help inform the new model.

As discussions about police reform dominated national and local conversations, Venuti reviewed past and present efforts to meet the community’s public safety needs in a holistic and inclusive way. While VCU Police had made strides in areas such as use of force, which has sharply declined in the past 10 years, Venuti was still looking for ways to make policing more equitable.

Training officers to respond differently

Today, a top priority is to better train officers to work with individuals with mental illness, particularly those in crisis.

“Looking at incidents across the country, conversations about mental health and what our officers handle on a daily basis, there was an opportunity for us to improve in this area,” Venuti says. “Someone who exhibits alarming behavior does not necessarily have criminal intent. They may need professional help, and we want our officers to be better prepared to recognize that difference.”

William Pelfrey, Ph.D., professor and chair of the homeland security and emergency preparedness program in VCU’s L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, says police are becoming de facto mental health responders for a variety of reasons.

“The lack of viable destinations for persons experiencing mental health crises has given police few placement options. In other words, police know that if they take a person with mental health issues into custody, they may have to escort that person for hours, sometimes spanning multiple shifts, before a placement location can be identified,” Pelfrey says. “Research has demonstrated the importance of crisis intervention training, particularly revolving around de-escalating complicated situations. Officers who participate in de-escalation training, including occasional refreshers, are more likely to deal with complicated situations effectively and equitably.”

As of March, VCU Police has trained all 95 officers and select staff in Crisis Intervention Training or Mental Health First Aid, an eight-hour course that teaches officers how to assess a situation, intervene appropriately and help someone find appropriate care. The department has met the International Association of Chiefs of Police One Mind Campaign’s criteria for CIT-trained officers and intends to train officers and dispatchers in Mental Health First Aid this spring.

Other training for officers and staff has included Implicit Bias, Gender Beyond the Binary, an introduction by VCU Inclusive Excellence to VCU’s Call Me By My Name initiative and the training of two additional Fair and Impartial Policing instructors within the department. Officers also complete training for diversity awareness and de-escalation techniques when they join the force and then biannually.

“Diversity awareness and de-escalation training have been useful for officers,” says VCU Police Patrol Sgt. Jennifer Riemann, who completed the trainings. “It helps them recognize potential barriers to effective communication and teaches them to overcome them in a way that is both empathetic and respectful to the individual they are trying to help.”

She adds that Implicit Bias and Fair and Impartial Policing training helps officers recognize factors they might not be consciously aware of and that have the potential to impact decision-making.

“By teaching officers how to recognize implicit biases, it trains them to take active steps to reduce implicit bias and ensures that we are being good stewards of safety for our community,” she says.

Hiring safety ambassadors as points of contact

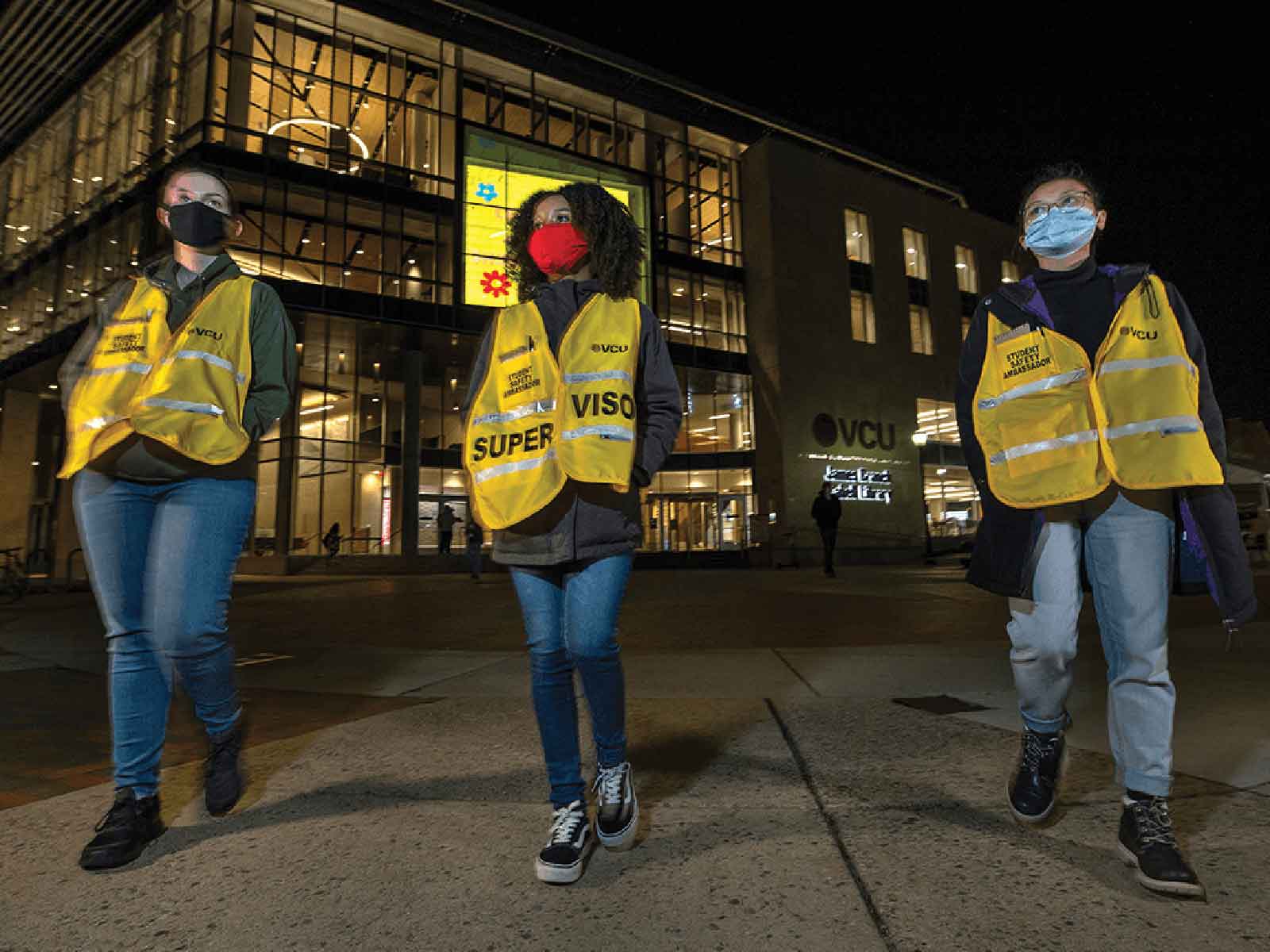

VCU Police hired three VCU students in the fall as safety ambassadors, another shift in methods and policy.

The students completed 40 hours of training and can help community members who might need assistance but don’t need — or in some cases, want — to contact police.

From Venuti’s perspective, students can be a better alternative than uniformed, armed officers for needs such as giving directions, answering questions about transportation, working at events and walking people to their cars at night. The students, who wear bright-yellow vests, also report safety concerns they come across during their nighttime shifts.

Safety ambassadors patrol high-traffic areas on the Monroe Park Campus, such as outside the University Student Commons and in the Compass. They’ve also worked shifts on the MCV Campus.

In cases where police are the best option, such as an emergency, the student ambassador contacts police dispatchers immediately.

“They are not responsible for traditional police work,” Venuti says.

VCU sophomore Ayanna Farmer-Lawrence was one of the first of three safety ambassadors hired. A homeland security and criminal justice major in the Wilder School, the part-time position coincides with her goal of becoming an agent for the FBI.

“I thought it was a good idea to be that person that [people] can go to if they have a problem but don’t want to go to the police directly,” Farmer-Lawrence told VCU News in November. “It’s a good idea given what’s going on in society currently.”

In their first two nights working, the safety ambassadors reported damaged property, a traffic light failure and a fire at a business on West Broad Street. More recently, they’ve made VCU Police aware of unauthorized entries into a VCU building and potential safety hazards, such as lights that are out around campus.

VCU Police plans to expand the number of student safety ambassadors to 10, and their designated locations, by the end of 2021.

Decreasing use of force by officers

An encouraging data point that Venuti cites: During the 2019-20 academic year, VCU Police recorded the lowest number of officer-involved use-of-force incidents in the past 10 years.

“Clearly, three factors are critical to successful policing in the 21st century: police legitimacy, which refers to the community’s trust in the department and likelihood of cooperating with police, de-escalation efforts and police accountability,” Venuti says. “We have consistently looked at ways to reduce use of force and increase efforts by officers to de-escalate situations.”

When Venuti started in 2010, he instituted data collection on use-of-force reports. The department had 75 incidents in 2009-10, and as of July 31, 2020, that number was down to 12 for the previous full academic year, an 84% reduction. A Transparency Dashboard on the police department’s website allows community members to view real-time data about officers using force.

The department formulated new use-of-force policies in 2015, updating them in 2017. The policies outline when officers should and should not use force and emphasize that if force is required, officers should always use the lowest level necessary.

“Back in 2015, we implemented many of the changes to our use-of-force policy that America is now calling for following the — what I would consider absolutely preventable — death of Mr. George Floyd in Minneapolis,” Venuti says. “We require officers to intervene to stop excessive force, and there is a duty to report excessive force. We do not allow chokeholds, and our policy clearly defines the use-of-force continuum as well as requires officers to de-escalate unstable situations.”

Edgar Greer (M.S.’17/GPA; Cert.’17/GPA) oversees nighttime patrol operations for VCU Police and says continuous training allows for a more direct understanding of the policy and the department’s expectations. The policy outlines what is known as the “use-of-force continuum,” he says, which is a standard guideline for law enforcement officers to determine how much force should be used against a person during a police interaction.

“VCU Police officers are trained to understand that use of force must be the officer’s last resort in any given situation,” Greer says. “The policy provides the officer with a directive on how to handle a situation. Additionally, it allows the department to parallel recent industry standards backed by case law.”

Policing through purposeful ideas

Venuti promotes a philosophy of “policing with a purpose.” He encourages officers and staff to focus on how they can use resources to proactively solve issues in the community instead of reacting once a problem has become unmanageable. If police see an uptick in bike thefts, for example, they launch a multifaceted approach to solve cases and prevent theft. As investigators work to identify bike thieves, community police officers might host outreach events to give away bike locks, and the department will use social media and the LiveSafe app to promote free locks and remind cyclists to use them.

That proactiveness is a two-way street, as the community also plays a role in developing innovative ideas to keep students, faculty, staff and visitors safe.

Shortly after Floyd’s death in late May, alumnus Terry Everett (B.S.’19/H&S) contacted VCU Police. Everett had worked with VCU Police as a student and says that while he had a close relationship with the department and interacted with officers, he also realized that “persons of color do not feel safe around police.”

“I really wanted to help and be a part of the voice of change,” Everett says.

He had the idea to create a channel for those being stopped by police, or for bystanders, to intervene in a situation they might feel is escalating or in which they think an officer is acting improperly. With Everett’s support, VCU Police implemented a “Check Police” button on the LiveSafe app in summer 2020. Users can click the “tip” option in the app and anonymously report concerns about an officer’s conduct. VCU Police dispatchers, who monitor LiveSafe around the clock, receive the tip immediately. Protocol mandates that dispatchers check in via radio with the officer and send a police supervisor to the scene to ensure that officers are handling an incident or traffic stop appropriately.

“It’s a way to make students feel safer,” Everett says, “so that incidents don’t get mishandled and backup comes sooner.”

Everett adds that nobody should feel like they’re being targeted by police.

“There’s a sense of helplessness when you don’t know who exactly to call. Sometimes bystanders would think, ‘Why would I call more police?’ but [this lets] students be connected to a higher authority,” he says.

With these practices and improvements in mind, the work to implement change continues.

“We welcome police reform, and my officers and civilian staff are very mindful about this movement in society,” Venuti says. “One officer asked to facilitate group discussions to have difficult, but necessary, conversations about racial issues. Officers of different backgrounds want to better relate to each other and community members. We will continue to welcome feedback and will deliver high levels of transparency, and accountability, as we work through reforms and manage safety.”

– Corey Byers is a contributing writer for the alumni magazine.